GRAFTING

A few days after the queen lays an egg, it develops into a tiny larva, is fed by the nurse bees and begins to develop at the bottom of the cell in which the egg was laid. The larva must be removed from the cell and placed into a larger queen cup in order to develop a queen cell. Grafting is this process of removing the larva from the worker bee size cell and placing it in the queen cup.

In order to graft efficiently, the breeder hive from which the larva are being taken must be managed by inserting an empty frame so the queen can lay enough eggs at one time to develop into a significant number of larva at the same age on a single frame. A one day old larva is about right for grafting but is so tiny as to be barely visible to the naked eye.

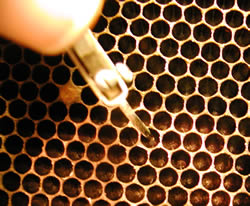

Before starting to graft, a number of plastic or beeswax queen cups are arranged on a wood bar and each cup is primed with a small amount of royal jelly. Using a specially made grafting tool with an end that resembles a tiny flat spoon, the larva is lifted out of the worker bee cell of the frame and deposited into the queen cup.